According to the Text, the Link Between Marriage and Family ______.

- Original Commodity

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Social relations and life satisfaction: the role of friends

Genus volume 74, Article number:7 (2018) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Social capital letter is defined equally the private's pool of social resources found in his/her personal network. A contempo study on Italians living as couples has shown that friendship relationships, beyond those within an individual's family, are an important source of support. Hither, we used information from Aspects of Daily Life, the Italian National Statistical Institute's 2012 multipurpose survey, to analyze the relation between friendship ties and life satisfaction. Our results show that friendship, in terms of intensity (measured by the frequency with which individuals see their friends) and quality (measured by the satisfaction with friendship relationships), is positively associated to life satisfaction.

Introduction

The concept of social majuscule and its analysis has attracted the attention of several disciplines (economics, folklore, psychology, etc.) in the past forty years. Starting from the seminal works of Coleman (1988), a multitude of social capital definitions and conceptualizations has been proposed (e.thou., Durlauf and Fafchamps 2005).

The primary concept present in all of the electric current definitions is that social capital is a resource that resides in the networks and groups which people belong to, rather than an individual characteristic or a personality trait. Portes (1998) divers social capital every bit "the ability of actors to secure benefits past virtue of their membership in social networks or other social structures," stressing that whereas "economical capital is in people'due south banking concern accounts and human upper-case letter is inside their heads, social majuscule inheres in the structure of their relationships" (p. 7). Lin et al. (2001, p. 24) divers social capital as "resource embedded in a network, accessed, and used by actors for actions."

The term "network" is used to draw the ties and social relationships in which an individual is embedded. A network is composed of a finite set of actors and the relations amongst them. There are two primary types of networks: complete and ego-centered. While complete networks describe the links between all members of a group, ego-centered networks are defined past "looking at relations from the orientation of a detail person" (Breiger 2004, p. 509), that is called ego, and therefore, ego-centered networks focus on an ego and his/her relations with a set of alters.

Recognizing the importance of identifying individuals' networks to empathize many phenomena (eastward.g., social support, socioeconomic mobility, social integration, health conditions), several national and international surveys (due east.g., the Generations and Gender Surveys, the International Social Survey Programme and the European Quality of Life Survey, and the Italian Multipurpose surveys) provide information on the ego-centered network of each respondent. This data might be used to investigate network-based sources of social capital at private level, even though these surveys are neither network-oriented nor social uppercase-oriented. Considering of the availability of these broad surveys that measure both social relations and aspects of an private's life, more studies have considered the potential role of social networks in the life of individuals.

One branch of research has focused on the link betwixt the characteristics and composition of social networks and the diverseness of support (emotional, material, and instrumental) available and/or received past individuals (Zhu et al. 2013; Amati et al. 2017). Another issue usually considered in the literature is the influence of an individual'due south social interactions on his or her behaviors, such equally fertility choices (Bernardi et al. 2007; Keim et al. 2009). Finally, the function of social networks on an individual'south well-being has besides been examined (Taylor et al. 2001; Haller and Hadler 2006; Powdthavee 2008).

The practical utilise of multipurpose surveys for the analysis mentioned above is conspicuously worthwhile. These types of surveys offer a large corporeality of data, allowing researchers to written report the role of social capital in a multifariousness of outcome variables controlling for individual and grouping-level characteristics. In the long term, repeated surveys might likewise provide longitudinal data for farther investigation on whether social upper-case letter and its role in an private'due south life change over time. The data collected from general surveys can likewise be analyzed to provide hints on certain phenomena (due east.thousand., quality of life, social and family life, lifestyle, friendship) when specific surveys are not available.

The electric current study supplements research that considers the role of resources embedded in a social network for an individual's subjective well-beingness. In this newspaper, a particular facet of social capital is analyzed: the function of friends equally alters in ego-centered networks (Breiger 2004). This pick stemmed from a contempo written report on Italians living in couple, which showed that friendship relationships are valuable sources of back up (e.grand., instrumental, emotional, and companionship) that supplement the back up inherent in traditional or expected ties to parents and relatives (Amati et al. 2015). This newspaper examines the role of friends in an individual'southward subjective well-being, which is measured past life satisfaction.

Data was obtained from the multipurpose survey "Aspects of Daily Life," collected by the Italian National Statistical Constitute (Istat) in 2012. The focus of the electric current study is on individuals aged 18–64 years former. This data allows investigation of friendship's effects on life satisfaction, measuring in terms of the frequency with which individuals see their friends (intensity) and the satisfaction with friendship relationships (quality). The underlying hypothesis is that friendship relationships influence life satisfaction through the potential (instrumental and emotional) resource that friends may provide. Those resources depend on both the presence of friends (measured in terms of frequency of meeting friends) and on the quality of the friendship (friendship satisfaction).

The paper is organized as follows: the "Background" section provides a review of the studies that considered the link betwixt friendship and life satisfaction, with particular attention on the importance of distinguishing friendship network characteristics in terms of intensity and quality of the relations with friends ("Quality and quantity in friendship relationships" department). Survey data and the strategy of analysis are described in the "Data and methods" section. Results are reported in the "Results" section and discussed in the "Final remarks" section.

Background

Social relations, friendship, and life satisfaction

Subjective well-being refers to the many types of evaluations that people make of their lives (Diener 2006) and is conceptualized and measured in unlike ways and with different proxies (Kahneman and Deaton 2010; Dolan and Metcalfe 2012).

Although life satisfaction is only i factor in the full general construct of subjective well-existence, it is routinely used as a measure of subjective well-existence in many studies (e.g., Fagerstrӧm et al. 2007; Ball and Chernova 2008; Shields et al. 2009). In particular, life satisfaction, referring to a holistic evaluation of the person'southward ain life (Pavot and Diener 1993; Peterson et al. 2005), concerns the cognitive component of the subjective well-beingness. Another commonly used measure for subjective well-being is happiness (Diener 2006), oftentimes used interchangeably with life satisfaction.

There is substantial evidence in the psychological and sociological literature that individuals with richer networks of active social relationships tend to be more satisfied and happier with their lives. This positive role of social relationships on subjective well-being may be explained past the benefits they bring. Kickoff, relationships, being key players in affirming an individual'due south sense of cocky, satisfy the basic human need for belongingness (Deci and Ryan 2002) and are a source of positive affirmation. The levels of subjective well-being increase with the number of people an individual tin trust and confide in and with whom he or she tin discuss problems or of import matters. On the other hand, these levels decrease with a surplus presence of acquaintances or strangers in the network (see Burt 1987; Taylor et al. 2001; Powdthavee 2008).

Second, the presence of social relationships has positive impacts on mental and concrete health, contributing to an private'due south full general well-existence, whereas the absence of social relationships increases an individual's susceptibility to psychological distress (Campbell 1981; Nguyen et al. 2015). Several studies have shown that social relations stimulate individuals to fight diseases (Myers 2000) and reinforce healthy behaviors (Putnam 2000). Social interactions have the potential to protect individuals at risk (e.g., encouraging them to develop adjustment techniques to face the difficulties) and promote positive personal and social development, which diminishes the exposure to various types of stress (Myers 2000; Halpern 2005) and increases the power to cope with it.

Finally, social relationships form a resource pool for an individual. These resource tin have several forms, such every bit access to useful information, company (e.g., personal and intimate relationships, time spent talking together, and shared amusement fourth dimension or meals), and emotional (eastward.g., advice about a serious personal or family affair) and instrumental (eastward.g., economic help, administrative procedures, house-keeping) support. Several studies have detailed how receiving support contributes to college well-being, although the effects may vary by the type and the provider(due south) of back up (Merz and Huxhold 2010). In a wider perspective, social relationships serve every bit buffers that diminish the negative consequences of stressful life events, such equally bereavement, rape, job loss, and illness (Myers 2000). The perceived availability of support or received support from others may, indeed, lead to a more benign appraisal of a negative state of affairs.

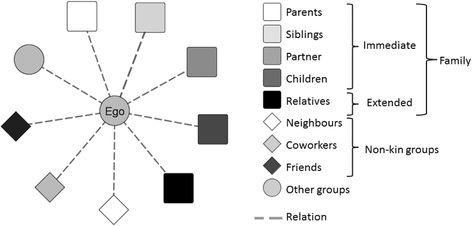

In this view, friendships, considered as voluntary relationships that involve a variety of activities, may contribute significantly to the overall subjective well-being (Clark and Graham 2005). Friends are only one of the possible alters in an ego-centered network, every bit represented by Fig. 1. At the aforementioned fourth dimension, they are the only alters that a person chooses every bit a node that belongs to his/her personal network while parents, siblings, and relatives are "the family you are born with", and neighbors and coworkers are people an individual usually encounters in a preexisting state of affairs, "friends are the family you lot choose" (Wrzus et al. 2012, p. 465).

Ego and kinds of alters in an ego-centered network

As for many relationships, friendship strongly depends on meeting opportunities (Verbrugge 1977; Feld 1981), as determined past social settings (Pattison and Robins 2002), and the decision of individuals to establish a sure friendship tie. This indicates that friendship is often related to positive interpersonal relationships which are important and meaningful to an individual and satisfy various provisions (intimacy, support, loyalty, self-validation). In improver, back up from friends is usually voluntary, sustained just by feelings of affection, mutuality, and love (Yeung and Fung 2007), but not motivated by moral obligations (typical of family ties, Merz et al. 2009).

Recent years witnessed the growth of social contexts where the importance of friends is increasing. First, sociodemographic changes, such every bit the reduction in the number of children in each family and a weakening of traditional communities like churches and extended families, raise the relevance of friends in the network (Suanet and Antonucci 2017). Second, family and marital relationships have also changed over the concluding few decades; through divorce and remarriage, they announced more complex and less robust. The breakdown of the immediate household and of the extended family tin can have straight implications on the relationships amidst the household members. Friends tin can substitute, in a sure sense, the traditional family unit (Ghisleni 2012), offering invaluable communication, support, and companionship.

Just the positive consequences of friendship on well-being have been considered so far. Yet, friendships might also play a negative part for an private's well-existence. Apropos the need for belongingness, some friends may be disturbed individuals and thus take a damaging effect on an individual (Halpern 2005); in add-on, the fear of existence criticized or excluded may also have a negative impact on well-beingness. As to the health motivation friends might encourage individuals toward unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking or overeating (Schaefer et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2014). Finally, unfulfilled expectations may negatively touch on the benefits derived from support. Despite these potentially negative influences, friendships are by and large expected to accept a positive role in an individual'due south well-being (Van Der Horst and Coffè 2012).

Quality and quantity in friendship relationships

Friendship relationships tin can recall both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. For example, asking almost having or not having friendship ties is often related to the count of the number of friends; similarly, evaluating the degree of common concern and interest calls for a quantitative measure, such as the elapsing of friendship or the frequency of interaction. Distinguishing between best friends and friends, existent or close friends, "actually true" or "not true" friends (Boman Iv et al. 2012) is qualitative measures of friendship relationships. The qualitative aspects are adamant by the fact that friendship relations might exist close, intense, and supportive at different levels. In general, the closer the friendship, the more evident the diverse qualitative attributes of friendship (Demir and Özdemir 2010).

The different definitions of friendship emphasize both the qualitative dimension and the interactive sphere of friendship. Alberoni (1984) divers friendship every bit "a clear, trusted, and confident feeling" (p.11). Hays (1988), based on a review of theoretical and empirical literature, suggested a more than comprehensive definition of friendship, wherein "a voluntary interdependence betwixt two persons over time, that is intended to facilitate socio-emotional goals of the participants, and may involve varying types and degrees of companionship, intimacy, affection, and mutual aid" (p. 395). The Encyclopedia Britannica defines friendship equally a "state of enduring affection, esteem, intimacy, and trust between two people" (Berger et al. 2017). All these definitions bespeak that friendship is recognized as a dyadic human relationship by both members of the human relationship and is characterized by a bond or necktie of reciprocated affection. Information technology is not obligatory, conveying with it no formal duties or legal obligations to i another, and is typically egalitarian in nature and almost always characterized by companionship and shared activities (Berger et al. 2017).

The network perspective emphasizes the dyadic nature of friendship and stresses the quantitative dimension of friendship relationships in terms of the "strength" of an interpersonal necktie, where "the strength of a necktie is a (probably linear) combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (common confiding), and the reciprocal services which narrate the tie" (Granovetter 1973 p. 1361).

The analysis of the interaction betwixt friendships and personal well-being or life satisfaction is strongly influenced by the available data, which often regards the quantitative dimension of friendships. Several studies accept emphasized how this dimension affects an individual's well-existence through the benefits friendship brings. In particular, a large number of friends, also as more contact with these friends and a low heterogeneity of the friendship network, are related to more social trust, less stress, and better health (McCamish-Svensson et al. 1999; Van Der Horst and Coffè 2012). From the indicate of view of support, having many friends and frequent contact with them increases the chance of receiving assistance when needed (Van Der Horst and Coffè 2012). More broadly, the frequency of meeting a friend can be an indicator of the strength or intensity of the relationship (Haines et al. 1996). Stronger relationships might imply increased knowledge of an private'southward needs, thus creating a stronger source of potential assist. Regarding the qualitative dimension, empirical research is quite scanty; yet, what is bachelor shows that satisfaction with a friendship is strictly related to an individual'southward well-being and life satisfaction (Diener and Diener 2009; Froneman 2014).

Taking into account both the questionnaire constraints and the inquiry focus on studying the role of friends in life satisfaction, this study focused on adulthood and measured the quantitative dimension of friendship through the intensity of interaction ("frequency of meeting friends") and the qualitative dimension through the satisfaction with friendship relationships. The hypotheses that the intensity of relations with friends might have a different result depending on the level of satisfaction with these relations were tested. A faithful frequency of contacts with friends, together with positive satisfaction with friendship relationships, connects individuals to a range of extra benefits, including a higher sense of belongingness, better health, and more back up (Van Der Horst and Coffè 2012).

Information and methods

The multipurpose survey "Aspects of Daily Life"

Data was fatigued from the cross-sectional, multipurpose survey "Aspects of Daily Life," carried out in Italia past Istat. Conducted annually since 1993, it is a big sample survey that interviews a sample of approximately 50,000 people in about 20,000 households. It collects information on several dimensions of life for each individual, including basic socio-demographic characteristics of individuals (age, sex, education) and of their households (socio-economic status and family structure) and information on health, lifestyle, religious practices, and social integration.

Starting in 2010, the survey investigated life satisfaction for individuals aged over 14, asking the following question: "How satisfied are you with your life on the whole at present?" Answers range betwixt 0 (not satisfied at all) and 10 (very satisfied). These levels of life satisfaction represent a crude measurement of the underlying continuous variable, i.e., life satisfaction, which cannot be measured on a continuous calibration.

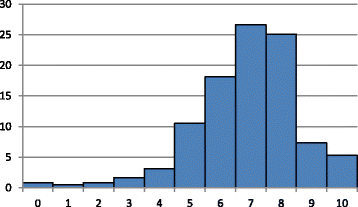

The current report focuses on the about contempo survey data (2012) and considers the life satisfaction of 25,190 individuals (ages 18–64). Figure 2 reports the percentage distributions of these individuals co-ordinate to their life satisfaction. It demonstrates that the proportions of individuals who declared indexes of life satisfaction nether 5 are quite depression; those with life satisfaction equal to 5, nevertheless, are not negligible. On the whole, only 17.five% of individuals declared a life satisfaction under 6. Most individuals (64.iv%) seem to be quite satisfied in their life, declaring values equal to or greater than 7.

Percentage distributions of individuals aged 18–64 according to their life satisfaction

Adjacent, to the question on life satisfaction, at that place are 2 additional questions collecting data on two different aspects of friendship relationships: the frequency at which individuals usually encounter their friends in their leisure time and the satisfaction of individuals with friendship relationships over the previous 12 months. The first aspect can be seen equally a proxy for the intensity of friendships interaction. Response options of the corresponding question consisted of ane = every day, 2 = more than once per week, iii = in one case per week, 4 = several times (but less than 4) per calendar month, 5 = sometimes per twelvemonth, half-dozen = never, and 7 = without friends. In the following analyses, these seven categories are grouped Footnote i to distinguish individuals meeting their friends as follows: more than in one case a week (1, 2), once a week or several times a calendar month (iii, 4), and less often or not having friends (five, 6, 7).

The second question concerns satisfaction of individuals with friendship relationships understood equally the quality of friendships. This satisfaction can be considered equally a proxy for the quality of friendship. The corresponding question response options consisted of i = very satisfied, 2 = quite satisfied, 3 = not very satisfied, and four = non satisfied at all. In the following analyses, the concluding two categories are grouped together because of the depression proportions of individuals indicating no satisfaction at all in friendships. Table 1 reports the distribution of individuals according to both of these key variables describing friendship. The data shows that most individuals run into friends more once a week and are quite satisfied with the friendship relationship.

Table 2 shows that friendship and life satisfaction are related. Individuals meeting their friends more often and declaring themselves more satisfied with their friendship relationships tend to have a college life satisfaction when compared to people who rarely meet their friend and/or are not satisfied with their relationships. In addition, the association between these variables describing friendship relationships and life satisfaction is statistically significant (χ 2 = 2288.two, df = 20, p value < 0.001 and χ 2 = 394.04, df = 20, p value < 0.001, respectively, for friendship satisfaction and frequency of contacts). However, these associations may be due to other compositional factors. Younger individuals encounter their friends more ofttimes than older ones, and literature has shown that life satisfaction is higher amidst younger people (Demir et al. 2015, Walen and Lachman 2000). Thus, the role of friendship has to exist examined using multivariate analyses, while decision-making for a series of other variables.

Methods and strategy of analysis

A multilevel logistic regression model was estimated to investigate the relation between life satisfaction (dependent variable) and the frequency of coming together friends and the satisfaction of friendship relationships (explanatory variables), decision-making for several covariates. The choice of a random intercept logistic regression model was motivated by both the data structure and the level of measurements of the dependent variable.

Specifically, the data shows a nested construction, where the first-level units are the individuals and the second-level units are the families. To control for the nested structure, we considered a multilevel model, rather than simply correcting the estimated standard errors for the presence of amassed units in the sample. The express number of individuals belonging to the same family (the 99% of the families has a size smaller than four) might be problematic for the methods because of the correction of the standard errors (Leoni 2009).

Regarding the dependent variable, the fact that it is measured on an ordinal scale should be considered. Several models have been proposed for the assay of ordinal variables, amid them the ordinal logistic regression model (Agresti 2010). This model is the extension of the multinomial logit model to ordinal variables. One of the central assumptions underlying the ordinal logistic regression model is the proportional odds assumption, requiring that the human relationship between each pair of outcome categories is the same. When this assumption is violated, the estimates might exist biased and the standard errors might exist either underestimated or overestimated, leading to misleading conclusions derived from ordinal regression models. An alternative is available in the fractional ordinal logistic regression model which relaxes the supposition of proportional odds, allowing the parameters to vary across the level of the dependent variables, simply yielding a less parsimonious model.

The analyzed data provides evidence against the assumption of proportional odds (χ 2 = 4456, df = 414, p value < 0.001); therefore, a partial ordinal logistic regression would exist adequate. Still, the number of categories of the dependent variable is far from negligible, and estimating such a model would yield a non-parsimonious model that is difficult to be interpreted. Consequently, we analyzed the association betwixt life satisfaction and the two dimensions of friendship in a standard multilevel logistic regression setting where the dependent variable is recoded into categories, obtained using different thresholds.

Several variations on recoding have been considered to test the robustness of the model to the choice of the threshold. Nosotros considered three binary categorizations, using threshold 6 (unremarkably conceived every bit "sufficiency," since it is the mark distinguishing between pass and neglect in tests at schoolhouse in Italy), seven (the mean satisfaction score in the sample), and 8, which is the threshold value used past Istat (2015, 2016). Later on that, the respective multilevel binary logistic regression was estimated. A categorization into iii levels (< 6, 6, and 7, ≥ 8) was also considered and a multilevel multinomial logistic regression model was used for the estimation. This model did not reach convergence considering of the high percentage (forty%) of second-level units (family), including only one offset-level unit of measurement (private). In the following, only the results deriving from the multilevel binary logistic regression, which is briefly described in the following lines, were reported.

Let N be the number of second level units and n j (j = 1,…, Due north) be the number of outset level units in grouping j. Allow Y ij denote the dichotomous variable taking value 1 if the life satisfaction of an individual is at least 7 and 0 otherwise. The two outcomes are coded every bit "satisfied" and "non satisfied", respectively. Variables that are potential explanations for Y ij are denoted by X ane, …, X chiliad. Let π ij exist the probability that an individual i in the group j is satisfied. A logistic random intercept model expresses the logit of π ij as a sum of a linear part of the explanatory variables and a random second-level (family unit)-dependent error ε 0j:

$$ \mathrm{logit}\left({\pi}_{\mathrm{ij}}\right)={\beta}_0+{\sum}_{thousand=ane}^p{\beta}_k{ten}_{\mathrm{kij}}+{\varepsilon}_{0\mathrm{j}}, $$

where β chiliad are statistical parameters that need to be estimated from the data.

Command variables

Post-obit previous studies (see for instance Huxthold et al. 2013), other explanatory variables were included in the model to let for consideration of the net association between life satisfaction and the two aspects of friendship. First, variables measuring potential social relations were included in the model. Results were controlled for the social integration and agile lifestyle. Social integration was inserted into the models considering of its importance for subjective well-being (as discussed in the "Social relations, friendship, and life satisfaction" section) and was measured considering the participation in meetings organized past political parties, trade union organizations, or by other (e.grand., voluntary or cultural) associations in the yr prior to the interview. Individuals who participated in at least one of these activities were distinguished from those with no participation. An active lifestyle was considered for its benefits on concrete and psychological health (meet, for instance, Hassmén et al. 2000). It was measured using a covariate that described concrete activities and distinguished individuals as follows: playing sports regularly, those engaged in concrete action at least once a calendar week, and those who were physically active less often or who were sedentary. Attendance at religious services was also included in the model, both for the social networks that people find in religious arrangement and for the private and subjective aspects of organized religion (Lim and Putnam 2010). This command variable is divers by iii categories of attendance: at to the lowest degree one time a week, sometimes in a month or in a year, and never.

Next, the multivariate analyses are controlled for a series of covariates grouped into three primary domains which the literature has shown to be important for life satisfaction (run across, for example, Siedlecki et al. 2008; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2015): socio-economic and demographic characteristics, health status, and personality traits. The socio-economic groundwork of individuals included their age, gender, education, employment status, and their family's economic situation and construction. Instruction is controlled for through a covariate with three categories: low (inferior high schoolhouse or lower), eye (secondary schoolhouse), and high (post-secondary education). Regarding employment status, we distinguished employed Footnote ii individuals from those who declared themselves to be unemployed and those who were out of the labor force (housewives, students, retired people, etc.). The family economic situation is measured through a question that subjectively evaluates family economic resource. A dichotomous covariate differentiated individuals in families with poor or insufficient resources from those with very proficient or good resources. Family structure was investigated keeping runway of both the type of family and an individual'southward position in the family. Individuals were distinguished as follows: individuals who are paired with another and with children, individuals who are paired with another without children, individuals who are children in households with at least ane parent, individuals who are parents in unmarried-parent families, and all other cases.

Health condition was measured because three subjective indicators of health: limitations, self-assay of health, and self-satisfaction with health. The first measured the presence of limitations and was based on individuals reporting any limitations on typical, day-to-day activities. These limitations were defined in three categories: severe limitations, only balmy limitations, and no limitations. The second indicator was obtained by a question asking individuals how they viewed their wellness; the five available responses were grouped into three categories: good (excellent or adept), fair, and poor (poor and very poor) wellness. The terminal subjective indicator was measured by an individual's satisfaction with health, grouped into 3 categories: very satisfied, quite satisfied, and not satisfied (including individuals who declared themselves every bit non very satisfied or non satisfied at all).

An individual's personality was identified through two indicators. The kickoff was obtained from a question investigating whether individuals trust people; the results distinguished those who alleged that most people can be trusted from those who thought that they must be very careful. The second indicator was obtained from a question request individuals for their views on futurity and personal situations, with four response options: the state of affairs will amend, it will remain the aforementioned, the state of affairs volition worsen, and "practise not know." In the analyses, the individuals were grouped into optimistic, pessimistic, and indifferent categories; the final merging people who did not know with those who alleged the situation will remain the aforementioned. Along the aforementioned lines, an individual's satisfaction on specific aspects of life, ranging from employment Footnote 3 and economical resources to family relationships and leisure time, was taken into business relationship by the model. Footnote four Identical to questions on friendship relationships, the respective response options consisted of the following: i = very satisfied, 2 = quite satisfied, three = not very satisfied, and iv = not satisfied at all. In the post-obit analyses, the last two categories are grouped as one.

Finally, the results were controlled for the geographical area of residence (north-west, n-east, center, and south), and the type of municipality (distinguishing, by manner of population count, metropolitan areas and suburbs from other towns) for the potential importance of economic, social, environmental, and urban development of the area in which individuals live (González et al. 2011).

Before estimating the model, associations amid the explanatory variables were checked using the normalized mutual data. All the values were shut to 0, thereby suggesting the absence of strong correlation among the control variables.

Results

As described in the "Methods and strategy of analysis" section, three thresholds accept been used to categorize the dependent variable and investigate the robustness of the model to the option of the threshold. The respective, multilevel logistic regression models pb to the same estimated effects, thereby indicating that the model is robust to the option of the threshold. Here, we report just the results Footnote 5 considering the threshold value seven (Tabular array 3). The appropriateness of the multilevel specification to account for the data structure as revealed by the intercept variance significance should be noted.

The demographic characteristics are considered first. Gender is not significant, suggesting that at that place are no differences in life satisfaction between men and women. The parameters associated with the age are both significant, suggesting that there is a quadratic relation betwixt life satisfaction and historic period. The linear combination of the estimates indicates that the oldest people tend to be more than satisfied than the youngest. It is observed that individuals with a high level of educational activity tend to be less satisfied than those possessing a lower or medium level of instruction. These results tin exist related to the dissimilar expectations the immature (more eager for life) and, to some extent, more educated people (more acute in the evaluation of their living atmospheric condition) accept with respect to those who are older and less educated. Regarding the age upshot, the difference with the aforementioned literature might be due to a diverse context of analysis and/or to the choice of other command variables.

The coefficients of the variables related to the economic status show that employed people (particularly those who declared to be very satisfied with their work) with acceptable economic resources tend to be more satisfied than the others. The coefficients related to the family'due south structure suggest that individuals living in couples (with or without children) tend to exist more satisfied with their life when compared to people living in other family structures.

Social integration and active lifestyle, with all its aspects, also play an important office. The more than integrated an individual is, the more satisfied he/she is, as suggested past the positive coefficient related to social integration. The model estimates too suggest that people attending religious services (regularly or sometimes in a year) tend to be more satisfied with their life than people non attending religious services. A similar upshot is observed for physical activities, where a moderate physical activity leads to higher life satisfaction. The negative coefficients of the health status, measured by the private subjective perception indicate that a worse health status correlates to a lower life satisfaction. Similarly, the coefficients related to the presence of limitations point that individuals with severe limitations tend to be less satisfied than those who practise not accept limitations.

An individual's personality traits as well impact life satisfaction. Trusting other people and having a positive attitude increase the probability of having loftier life satisfaction. Similarly, the data suggests that an individual'south high satisfaction with facets of their life (economic, wellness and family relationships, and costless time) correlates to a higher life satisfaction.

Finally, the coefficients related to variables concerning the geographical expanse individuals live in suggest that living in the north-west area increases the probability of beingness satisfied. For the type of municipality, the model suggests that individuals living in a town with more than 2000 inhabitants, but less than 10,000, take a higher probability of existence satisfied.

The coefficients related to the key variables showed that friendship relationships were associated with life satisfaction. In particular, the probability of an individual who meets friends one time a week or several times a month being satisfied with life is 9% lower than the same probability for an individual who meets his friends regularly. If the private meets friends but a few times a year or does not have friends, then the probability of being satisfied decreases virtually 27%. Moreover, if individuals are either quite satisfied or not satisfied with their friendship relationships, so the probability of beingness satisfied decreases 49 and 69%, respectively, compared to the same probability for individuals satisfied with their friendship relations. We also tested the presence of several interaction effects. Start, a synergy consequence between the frequency of meeting friends and the friendship satisfaction was checked for. This enabled testing if frequent and satisfactory friendship relations might increase the probability of being satisfied with life. The corresponding parameters turned out to be not significant.

In addition, the interaction between type of municipality and friendship satisfaction and intensity of friendship, respectively, was considered. The motivation relies on the fact that many network studies (e.g., Adams et al. 2012), aiming at defining the outcome of the geographical infinite on the configuration of the network, have suggested that smaller areas and proximity facilitate contacts and are contexts where people get to know each other more easily. The assay indicated that only the interaction betwixt existence not satisfied and living in a small expanse was negative and significant. Since all the other interactions were not significant, and the conclusions for all the other variables did not change when including or excluding interactions, but the more than parsimonious models without interactions are reported in the newspaper.

Concluding remarks

The assay of social upper-case letter focuses on the set up of relationships in which individuals are embedded. These relations are resources for the individuals themselves and might take an bear on on some aspects of their life, e.g., performance, well-being, and support.

An analysis of a item facet of social uppercase, namely the role of friendship relations on the life satisfaction of people aged 18–65, was conducted. Using data from the multipurpose survey "Aspects of daily life," collected by the Italian National Statistical Institute in 2012, a multilevel logistic model was estimated to written report the link between life satisfaction and the frequency of meeting friends, besides as the satisfaction with friendship relationships. This link is considered, past psychological literature, as a bidirectional dynamic process (Demir et al. 2015). Having friends and close peer experiences are both important predictors of life satisfaction, and satisfied individuals tend to have stronger and more intimate social relationships.

Although in the current report the target variables follow a partially logical chronological guild, the data derives from an observational study, and therefore, no causal relations tin be inferred. Consequently, we only focused on the clan between life satisfaction and friendship decision-making for all other potential confounding variables that we have at disposal. This is a limitation of the study that may only be addressed using longitudinal data.

The results of the analysis showed that less frequent meetings contributed to lower friendship relationship satisfaction, thus leading to lower life satisfaction. These findings were robust to the choice of different thresholds and to a wide gear up of command variables—with significant associations—pertaining to iii main domains that literature has shown to bear upon life satisfaction.

The current study supports the finding that friends are relevant nodes in a personal network. A loftier life satisfaction is indeed associated with the presence of friendship. This might be explained past the positive functions attributed to friends. As suggested by previous enquiry, friends provide companionship (in addition to more social trust and less stress), intimacy, and assist, which increase an individual'southward life satisfaction (see, for instance, Demir and Weitekamp 2007).

Furthermore, the results bespeak that both having/meeting friends and good-quality friendship relations are important to an overall life satisfaction. Individuals may do good from positive interactions with friends, which are a part of an private's social uppercase. Loftier-quality friendships are more likely to be characterized by support, reciprocity, and intimacy. Conversely, low-quality relations and/or the lack of positive interaction may elicit feet.

The importance and the bear on of friendship on the life of individuals indicate that information technology is worthwhile to deepen the topic of friendship relationships and the "contexts in which such relationships are embedded" (Adams and Allan 1998). A study of the impact could also be benign in population studies. Similar all other types of personal relationships, friendships are indeed "constructed-developed, modified, sustained, and ended—by individual acting in contextual setting" (Adams and Allan 1998, p.three), which is defined by age, gender, stage of life, living arrangement, and experiences lived. These settings might affect the mechanisms of friendship formation and label in different ways and, consequently, the measurement of quantitative and qualitative dimensions of friendships.

Notes

-

This categorization has been suggested past preliminary analyses which considered all the seven categories and showed not meaning differences between categories 1 and 2, betwixt 3 and 4, and across categories 5, 6, and 7.

-

For employed individuals, besides their satisfaction with work is considered, distinguishing those very satisfied, those quite satisfied, and those non satisfied; this follows the perspective suggested below to consider also the individuals' satisfaction with dissimilar aspects of their life.

-

As mentioned in a higher place, satisfaction with work is embedded in the variable describing employment status (see footnote two).

-

There might exist a reversed relationship between life satisfaction and satisfaction in the different domains of private's life. While on the one hand, satisfaction in domains of life might affect life satisfaction; on the other hand, overall life satisfaction might impact individual's satisfaction. The issue of reverse causality has been discussed in the literature starting from the distinction betwixt top-downwardly and bottom-upwardly theories of well-being past Diener (1984) and has not yet been settled past the empirical research (encounter, for example, the word in Møller and Saris 2001; Rojas 2006; González et al. 2010). In the current analysis, nosotros aim only at investigating the association between satisfaction in the different domains of private'southward life and life satisfaction. The written report of bidirectional causal relation between life satisfaction and friendship relations is beyond the aims of the current newspaper. In fact, probably with the electric current information, there is not the problem of reversed human relationship between satisfaction in the unlike domain of individual's life and life satisfaction; in the questionnaire, indeed, the time reference of the different domains of individual life was the concluding 12 months, whereas the evaluation of life satisfaction was referred to the "usual" or "normal" behavior of the respondents without a precise time reference, and thus the old aspects are referred to a time that preceded the fourth dimension reference of life satisfaction.

-

The models were estimated using the process GLIMMIX in the programme SAS.

References

-

Adams, J., Faust, K., & Lovasi, G. South. (2012). Capturing context: integrating spatial and social network analyses. Social Networks, 34, 1–v.

-

Adams, R. G., & Allan, Thousand. (1998). Placing friendship in context. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press.

-

Agresti, A. (2010). Analysis of ordinal categorical information (2d ed.). Hobo- ken: John Wiley & Sons.

-

Alberoni, F. (1984). 50'amicizia. Milano: Garzanti.

-

Amati V., Meggiolaro S., Rivellini Thou., Zaccarin S., (2017) Relational Resource of Individuals Living in Couple: Evidence from an Italian Survey. Social Indicators Research 134 (2):547-590

-

Amati, Five., Rivellini, G. & Zaccarin (2015). Potential and Effective Support Networks of Young Italian Adults, Social Indicators Research 122(3): 807-831 .

-

Ball, R., & Chernova, K. (2008). Accented income, relative income, and happiness. Social Indicators Inquiry, 88(three), 497–529.

-

Berger L., Hohman L., Furman West. F. (2017), Friendship, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2017.

-

Bernardi, Fifty., Keim, S., & Von Der Lippe, H. (2007). Social influences on fertility. A comparative mixed methods study in Eastern and Western Germany. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(ane), 23–47.

-

Boman 4, J. H., Krohn, Thousand. D., Gibson, C. L., & Stogner, J. M. (2012). Investigating friendship quality: an exploration of self-control and social control theories' friendship hypotheses. Journal of youth and adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9747-x.

-

Breiger, R. L. (2004). The analysis of social networks. In M. Hardy & A. Bryman (Eds.), Handbook of data analysis (pp. 505–526). London: Sage.

-

Burt, R. Southward. (1987). A note on strangers, friends, and happiness. Social Networks, 9, 311–331.

-

Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-beingness in America: recent patterns and trends. New York: McGraw-Hill.

-

Clark, M. S., & Graham, S. Thousand. (2005). Do relationship researchers neglect singles? Can we do better? Psychological Inquiry, 16, 2/3, 131–136.

-

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

-

Deci, East. 50., & Ryan, E. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination inquiry. Rochester: Academy of Rochester Press.

-

Demir, M., Orthel-Clark, H., Özdemir, M., & Özdemir, South. B. (2015). Friendship and happiness among young adults. In M. Demir (Ed.), Friendship and happiness, Across the life-span and cultures (pp. 117–129). Dordrecht: Springer.

-

Demir, Thou., & Özdemir, M. (2010). Friendship, need satisfaction and happiness. Periodical of Happiness Studies, 11, 243–259.

-

Demir, M., & Weitekamp, L. A. (2007). I am then happy 'cause today I found my friend: friendship and personality as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), 181–211.

-

Diener, Due east. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

-

Diener, Due east. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-beingness. Applied Research in Quality of Life, ane, 151–157.

-

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. In Editor (Ed.), Civilization and well-being (pp. 71–91). Springer Champaign IL USA: Springer Netherlands.

-

Dolan, P., & Metcalfe, R. (2012). Measuring subjective well-being: recommendations on measures for use by National Governments. Periodical of Social Policy, 41(2), 409–427.

-

Durlauf, S. North., & Fafchamps, One thousand. (2005). Social capital. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economical growth, edition i, book 1, chapter 26 (pp. 1639–1699). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

-

Fagerstrӧm, C., Borg, C., Balducci, C., Burholt, V., Wenger, C. Thousand., Ferring, D., Weber, Grand., Holst, 1000., & Hallberg, I. R. (2007). Life satisfaction and associated factors among people aged sixty years and above in 6 European countries. Practical Inquiry in Quality of Life, 2(one), 33–50.

-

Feld, Due south. (1981). The focused organization of organizational ties. American Journal of Folklore, 86, 1015–1035.

-

Froneman, M. (2014). The relationship between the quality of a all-time friendship and well-being during emerging adulthood, primary of science (clinical psychology). University of Johannesburg Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10210/13740.

-

Ghisleni, One thousand. (2012). Amicizia east legami di coppia. In Thou. Ghisleni, S. Greco, & P. Rebughini (Eds.), L'amicizia in età adulta. Legami di intimità eastward traiettorie di vita. Milano: Franco Angeli.

-

González, E., Cárcaba, A., & Ventura, J. (2011). The importance of the geographic level of assay in the assessment of the quality of life: the instance of Spain. Social Indicators Enquiry, 102(ii), 209–228.

-

González, 1000., Coenders, G., Saez, Chiliad., & Casas, F. (2010). Non-linearity, complexity and limited measurement in the relationship between satisfaction with specific life domains and satisfaction with life as a whole. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 335–352.

-

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 81, 1287–1303.

-

Haines, Five. A., Hurlbert, J. S., & Beggs, J. J. (1996). Exploring the determinants of support provision: provider characteristics, personal networks, customs contexts and back up following life events. Journal of Wellness and Social Behavior, 37, 252–264.

-

Haller, Grand., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures tin can produce happiness and unhappiness: an international comparative assay. Social Indicators Inquiry, 75, 169–216.

-

Halpern, D. (2005). Social capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

-

Hassmén, P., Koivula, Northward., & Uutela, A. (2000). Physical practice and psychological well-being: a population study in Republic of finland. Preventive Medicine, xxx(1), 17–25.

-

Hays, R. B. (1988). Friendship. In S. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships. Theory, research and interventions. London: John Wiley & Sons.

-

Huang, Thousand. C., Soto, D., Fujimoto, K., & Valente, T. West. (2014). The interplay of friendship networks and social networking sites: longitudinal analysis of choice and influence furnishings on adolescent smoking and alcohol utilise. American Periodical of Public Health, 104(viii), 51–59.

-

Huxthold, O., Miche, M., & Schz, B. (2013). Benefits of having friends in older ages: differential effects of informal social activities on well-being in middle-aged and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Serial B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(3), 366–375.

-

ISTAT. (2015). Rapporto Annuale 2015, La situazione del Paese. Roma: Istat.

-

ISTAT. (2016). Rapporto Bes 2016: Il Benessere equo eastward sostenibile in Italia. Roma: Istat.

-

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of the life but non emotional wellbeing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

-

Keim, S., Klämer, A., & Bernardi, 50. (2009). Qualifying social influence on fertility intentions composition, structure and meaning of fertility-relevant social networks in Western Frg. Electric current Folklore, 57(6), 888–907.

-

Leoni, E. L. (2009). Analyzing multiple surveys: results from Monte Carlo experiments (pp. 1–38). Ms. Columbia University.

-

Lim, C., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review, 75(half-dozen), 914–933.

-

Lin, Northward., Fu, Y., & Hsung, R. (2001). The position generator: a measurement instrument for social capital. In N. Lin, K. Melt, & R. Burt (Eds.), Social capital letter: theory and research (pp. 57–81). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

-

McCamish-Svensson, C., Samuelson, Thousand., Hagberg, B., Svensson, T., & Dehlin, O. (1999). Social relationships and health as predictors of life satisfaction in advanced old age: results from a Swedish longitudinal study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 48(4), 301–324.

-

Meggiolaro, Southward., & Ongaro, F. (2015). Life satisfaction amongst older people in Italian republic in a gender approach. Ageing & Gild, 35(7), 1481–1504.

-

Merz, East. G., Consedine, N. S., Schulze, H. J., & Schuengel, C. (2009). Wellbeing of adult children and ageing parents is associated with intergenerational support and relationship quality. Ageing & Society, 29(5), 783–802.

-

Merz, Eastward. Thou., & Huxhold, O. (2010). Well-existence depends on social relationship characteristics: comparing different types and providers of support to older adults. Ageing & Society, thirty(five), 843–857.

-

Møller, 5., & Saris, W. E. (2001). The relationship betwixt subjective well-beingness and domain satisfactions in South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 55, 97–114.

-

Myers, D. Yard. (2000). The funds, friends, and organized religion of happy people. American Psychologist, 55(1), 56–67.

-

Nguyen, A. W., Chatters, Fifty. M., Taylor, R. J., & Mouzon, D. M. (2015). Social support from family unit and friends and subjective well-being of older African Americans. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10902-015-9626-eight.

-

Pattison, P. Due east., & Robins, G. L. (2002). Neighbourhood based models for social networks. Sociological Methodology, 32, 301–337.

-

Pavot, W., & Diener, Due east. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life calibration. Psychological Assessment, five, 164–172.

-

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, One thousand. E. P. (2005). Orientation to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, half dozen, 25–41.

-

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modernistic sociology. Almanac Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24.

-

Powdthavee, North. (2008). Putting a cost tag on friends, relatives, and neighbours: using surveys of life satisfaction to value social relationships. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(4), 1459–1480.

-

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling lonely: the plummet and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

-

Rojas, M. (2006). Life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life: is it a unproblematic human relationship? Periodical of Happiness Studies, seven(iv), 467–497.

-

Schaefer, D. R., Haas, S. A., & Bisho, N. J. (2012). A dynamic model of Usa adolescents' smoking and friendship networks. American Journal of Public Wellness, 102(6), 12–18.

-

Shields, Yard. A., Toll, S. W., & Wooden, G. (2009). Life satisfaction and the economic and social characteristics of neighbourhoods. Journal of Population Economics, 22(two), 421–443.

-

Siedlecki, K. L., Tucker-Drob, E. M., Oishi, S., & Salthouse, T. A. (2008). Life satisfaction across machismo: different determinants at different ages? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 153–164.

-

Suanet, B., & Antonucci, T. C. (2017). Cohort differences in received social support in later life: the office of network type. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(four), 706–715.

-

Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Hardison, C. B., & Riley, A. (2001). Breezy social support networks and subjective well-being amongst African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 27(four), 439–463.

-

Van Der Horst, G., & Coffè, H. (2012). How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. Social Indicators Inquiry, 107(3), 509–529.

-

Verbrugge, L. G. (1977). The structure of adult friendship choices. Social Forces, 56, 576–597.

-

Walen, H. R., & Lachman, M. Eastward. (2000). Social back up and strain from partner, family, and friends: costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Periodical of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, v–30.

-

Wrzus, C., Wagner, J., & Neyer, F. J. (2012). The interdependence of horizontal family relationships and friendships relates to college well-beingness. Personal Relationships, xix, 465–482.

-

Yeung, Grand. T. Y., & Fung, H. H. (2007). Social support and life satisfaction amid Hong Kong Chinese older adults: family first? European Journal of Ageing, 4(four), 219–227.

-

Zhu, X., Woo, S. E., Porter, C., & Brzezinski, Thou. (2013). Pathways to happiness: from personality to social networks and perceived support. Social Network, 35(3), 382–393.

Acknowledgements

The authors would similar to give thanks the Editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and necessary amendments on full general and technical bug that led to many improvements in this piece of work.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Non applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were fabricated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this commodity

Cite this article

Amati, V., Meggiolaro, S., Rivellini, G. et al. Social relations and life satisfaction: the function of friends. Genus 74, 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-018-0032-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-018-0032-z

Keywords

- Social capital

- Multipurpose survey

- Friendship relationships

- Life satisfaction

Source: https://genus.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41118-018-0032-z

0 Response to "According to the Text, the Link Between Marriage and Family ______."

Post a Comment